The Future is Now

Bifrost Online has launched to coincide with the two-year anniversary of the Paris Agreement on climate change, which was signed on 12 December 2015. The agreement was a landmark achievement of coordinated global action on environmental change, based on extensive data and findings collected from the international scientific community and evaluated rigorously in the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The Paris Agreement would have been impossible without the establishment of the IPCC, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Conference of the Parties to that convention (in this case COP 21), where 195 nations came together to support a number of goals guided by a single idea. The number of signatory nations eventually grew to 197, of which 170 have now ratified the agreement at the time of its two-year anniversary. The agreement gained legal force on 4 November 2016.

In his interview with the Bifrost team Bruno Latour reflects on what he calls “the amazing invention” of today’s international climate assessment and governance regime. “Geopolitically,” Latour notes, “the invention of the COP and of the IPCC is an amazing diplomatic invention and it should be protected and celebrated.”

In reality this regime is not a single system at all, but rather a dynamic interlinking of several distinct sectors of activity and influence—science, diplomacy, governance and activism foremost among them—that have come together, born of necessity.

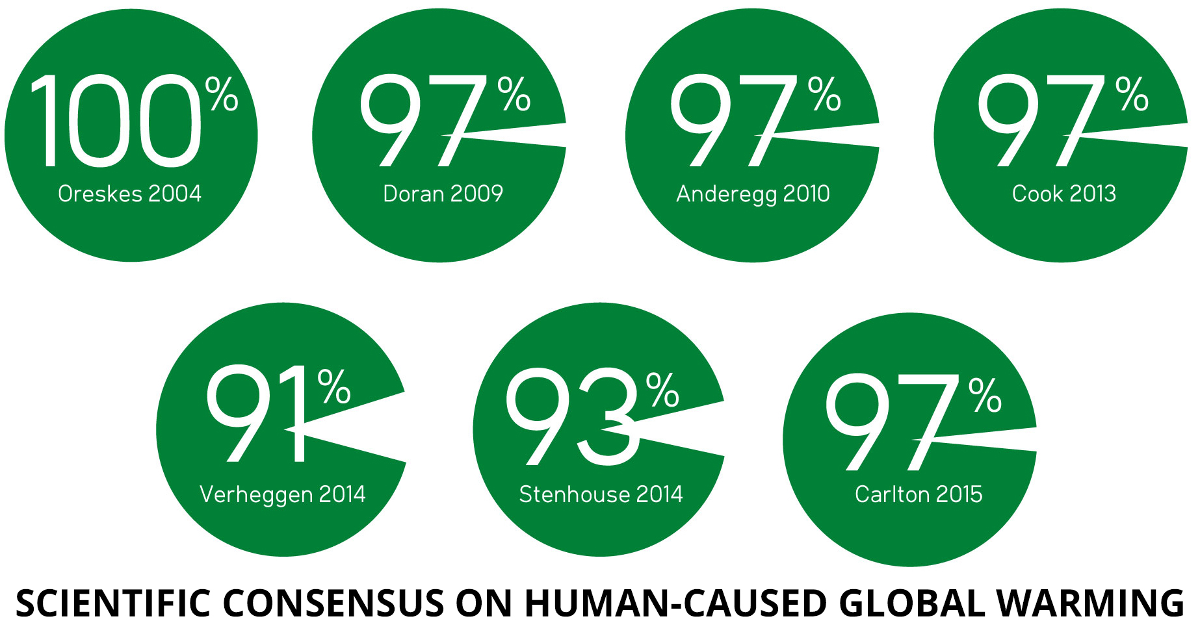

The mother of this invention was a growing concern at the intersection of science and public policy that began to take hold in the 1980s over observations that the earth, our only planetary home, was steadily warming as a result of escalating (human-caused) greenhouse gas emissions. The general scientific consensus, which also steadily grew over the following decades, held that the greenhouse effects of these emissions, if left unchecked, would sooner or later lead to a tipping point. A cascade of impacts and changes in the earth system could well follow, altering the conditions of life on the planet in ways highly challenging for humanity and unsustainable (potentially catastrophic) for untold numbers of other species.

Such public concerns triggered rapid international deployment of scientists, diplomats, and policy-advisors within a new framework for collaboration that represents a signal human accomplishment of the past few centuries. In seeking to hold the global average temperature increase to well below 2 °C (and aspirationally below 1.5 °C) above pre-industrial levels, the agreement was controversial in some quarters for a range of different reasons, but overall the international community embraced it as a step forward that was necessary and overdue. There are compelling recent studies and articles suggesting that the ultimate goal of keeping global mean temperature rise below the 1.5 °C mark will be extremely difficult if radical and globally widespread transformative action is not realized within the next 2-3 years.

One of the hard questions we must continually ask ourselves is to what extent we can avoid extreme to catastrophic climate change impacts in the world within a near future. The simple truth is that we are already experiencing extreme to catastrophic impacts in our world linked to climate change.

An article in The Guardian the same year the Paris Agreement was reached noted that 14 of the 15 hottest years on record had occurred since the year 2000, according to the latest figures then available from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Each of the following two years (2015 & 2016) then managed to eclipse the previous hottest year on record. Now according to the latest WMO figures, 2017 seems on track to give these last two years a run for their money.

It shouldn’t be necessary in light of these kinds of developments to suggest that there is a connection between current and recent global temperatures and the last series of natural disasters that have been in the public eye this year, whether they be the droughts and devastating wildfires in Australia or Western North America, sea-level rise and flooding in Bangladesh or Texas, unprecedented glacial melting in Greenland, or the most recent devastating hurricane season in the Caribbean.

These occurrences will all be eclipsed, and then eclipsed again, in the years to come. The increasing frequency and severity of just these kinds of events are precisely the kinds of effects the world has been advised to expect in the future if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. These prognoses are expressed with slightly varying but generally high degrees of confidence in the IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report and in other national climate assessments that feed into today’s international climate assessment and governance regime.

In 1988 Dr. James Hansen, then Head of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, testified about the potential threats of global warming before the U.S. Congress. His alarming testimony was one of the earliest high-profile warnings on this topic from a prominent member of the scientific community. Ever since this landmark wake-up call, public debate about climate change has remained focused on possible future scenarios. The science of climate change is more authoritative than ever, and the new political reality that this fact holds for the community of nations is clearer than ever. The Paris Agreement is itself evidence of that reality.

Almost three decades have passed since James Hansen lectured the U.S. Congress on the risks the world would face if we did not do something about the global warming trend. The earliest predicted effects of a continued warming trend, stemming from unchecked fossil-fuel emissions, are now observable in our world. Directing our imaginations to consider scenarios decades or half a lifetime in the future has, for many of us, insulated us from the reality of those abstractions. In thinking so much about future scenarios, if we have thought about them at all, the changes unfolding in the world around us have to some degree become normalized. The future we have been warned of is upon us. That future is now.

Anniversaries are useful things. They remind us to stop and look back, to consider where we were at the moment we are remembering. They give us reason to pause and consider where we have come since that moment. They may also encourage us to think where we are headed next. There is so much that has happened since the landmark agreement in Paris. Who could have predicted just two years ago the Brexit decision or Donald Trump’s meteoric rise to become the President of the United States? Who could have predicted the USA’s declared intent, under Trump’s new leadership, to withdraw from the Paris Agreement?

But not all developments are so disheartening. Some give renewed cause for hope. For example, something quite remarkable happened when Donald Trump announced he was planning to pull the U.S. of out the Paris Agreement. Actually, it began to take shape even before that announcement, as if this kind of move was anticipated from an administration that seemed to take a perverse pleasure in trolling its own citizenry. This is the administration, after all, that appoints new heads to major federal agencies and departments who have built careers on being antagonistic to these very institutions, to displaying outright hostility to the very reasons why these agencies exist in the first place. And so we have seen one overt climate change denier after another appointed to the agencies that set the country’s environmental agendas and priorities—the EPA, the Department of Energy, the Department of the Interior, and many more.

What happened even before Donald Trump announced his decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement was that governments of major cities and many states in the U.S. began to come together in strategic consortia, signaling their intentions to do their part to make sure the USA could meet the country’s obligations under the terms of the Paris Agreement, whether or not the U.S. federal government abandoned its mantel of responsibility.

Other companies and organizations have since begun to follow suit, and there is hope that new forms of organizing to act can achieve what the old forms may be too vulnerable to achieve. And there are other signs of hope and creativity. Production of renewable energy from wind and solar power has outstripped projections and expectations and that trend seems to be continuing. Together with Dr. James Hansen, twenty-one youth have sued the United States federal government for violating the public trust in failing to act on the threat of climate change. If this initiative, led by Our Children’s Trust, survives the Trump administration’s last-ditch attempts to hobble their case by keeping it from reaching the expected trial date in 2018, we will have an opportunity to witness what author Naomi Klein has called “the most important lawsuit on the planet” as it plays out in U.S. federal court.

We live in times of increasing uncertainty. The glut of white noise inundating social media, amid competing reports of fake news and alternative facts, can easily make the challenges facing the planet seem distant, abstract, overwhelming. We need to face our challenges. But we also need new forms of action, new ways of organizing ourselves, new ways of taking responsibility for the state of the world that we belong to. Creativity, ingenuity, inspiration, ethical and practical advice, all of these are every bit as important as scientific knowledge to the solutions we must forge in these climatically uncertain times. We need to connect to the stories and situations of individuals working to find their way, as we must all do.

Bifrost Online aims to bring reliable information, facts, knowledge, and lessons about environmental change and socio-ecological challenges to a community looking to connect. The project also aims to offer thought-provoking stories, art work, interviews and the wisdom of individuals with knowledge to share, whether in the form of scientific expertise or lived personal experience.

The Paris Agreement has given the world a framework. The rest is up to us. The future may seem distant and abstract, but it doesn’t have to be. It’s all around us and it’s what we gather from within ourselves. It’s what we make of the present.

The future is now.