Drowning Monuments

Drowning Monuments is a project that has been in my imagination for a very long time. As someone who has lived in New York City all my life, who has played violin for as long as I can remember, and who has grown up in an era of increased political and ecological turmoil, this project is a coming-together of so many parts of my world and identity, both as a citizen and as an artist. For many years, but especially after Hurricane Sandy blew through New York in 2012 (when I was a sophomore in high school), I have thought about playing music in places that are increasingly threatened by flooding and submersion due to global warming as a way of both calling attention and connecting audiences emotionally to the urgency of the climate crisis. This year, during the final stages of my undergraduate studies at The Juilliard School, I took a seminar entitled “The Arts and Society” with the new President of the school, Damian Woetzel, and was given the platform to realize these imagined possibilities.

As I began to consider what kind of music might be capable of speaking (without words) to broad audiences about these threatened places and the risks of rising sea levels, I felt that it was critical to find pieces that were both intensely relevant and authentic to the subject. In other words, I did not want to repurpose or posthumously assign relevance to works from the classical canon that were written decades (if not centuries) ago, but instead find music that reflected precisely our current moment and surroundings. And so, despite my love for Bach and Beethoven, I enlisted five of my talented peers from Juilliard to write new short works for solo violin (one for each of the five boroughs of New York City). I shared many of my ideas with the composers about the overall arc of the project, but ultimately I let them follow their own artistic instincts and interests as they considered how to translate the uncertainty of climate catastrophe into music. What emerged as I received the five pieces over the next month was remarkable. Beyond the musical thought and depth within each piece individually, together they began to form a cohesive story, each occupying a place on the spectrum of emotions that is provoked when we are confronted by the magnitude of this threat to our planet.

With the music beginning to take shape, I turned my attention to the visual component of the project. Although as a musician I deeply believe that music has the ability to move, inspire change, and transcend barriers in and of itself, I also believe that through artistic collaboration new forms of communication can be discovered and that each discipline can support and enhance the emotional impact of the other. In this spirit, I partnered with the extraordinary New York and Tel Aviv-based photographer and video artist Hinda Weiss to capture and create visuals which could facilitate a deeper sense of connection between the audience and the five chosen locations.

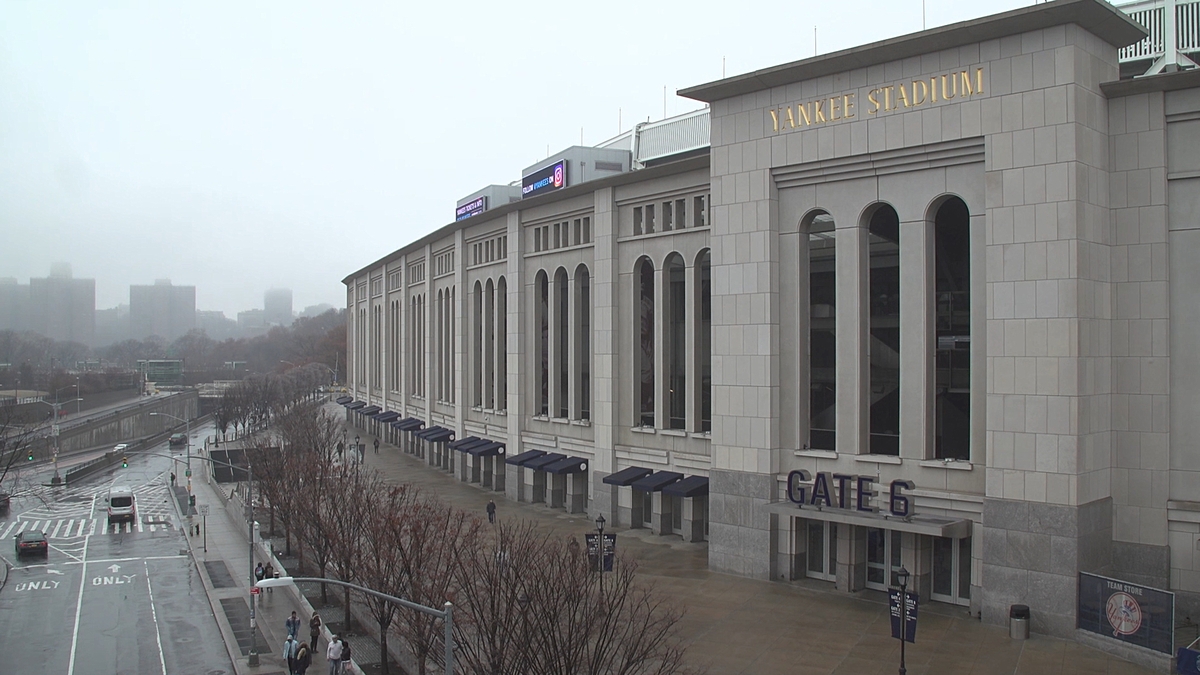

Despite the grand scope and dream of this project, the production process was remarkably condensed and low-budget. The constraints were certainly challenging, but they ultimately lent a wonderful vitality and artistic spontaneity to the whole process. I recorded the five pieces in one evening, with just myself and the composers in a dance studio at Juilliard. The next morning, I woke up early before my classes, hopped on the subway, and roamed the streets of lower Manhattan and Williamsburg in order to find and plan the shots we would take the following day. Hinda and I carried her tripod and camera across the five boroughs over the course of one weekend as we improvised shots and dodged the December rain. For one of the shots at Yankee Stadium, Hinda went up to the elevated subway platform tracks and stood on a bench so that her camera could peek through the wire mesh to film me as I stood below, waiting for her text to tell me that a train had passed and we could capture some footage. Another shot, the opening image of the Staten Island Ferry, was caught just after we disembarked and ran to film the ferry we had just left from the pavilion at the terminal. All in all, the video was filmed and edited in less than 48 hours — a testament to Hinda’s astonishing talent and ability.

I’ve lived in New York my entire life, and walking the streets and playing violin in places where my children or grandchildren may not be able to stand elicited a visceral sense of impending loss. But this project is not about mourning what is already lost or resigning ourselves to a drowned world. Instead, it strives to capture (both visually and sonically) the beauty and power of these places and the emotional attachments we have to them, and thus prompt a deeper consideration and conversation about how we (as artists and citizens, as city-inhabitants, as a global community) are planning for the future. I see Drowning Monuments as the beginning of an expansive and far-reaching project with longer pieces, multi-disciplinary collaborations, and deeper engagement with scientific communities — all aiming to face this crisis with fierce creativity and conviction, and with the full force of the arts and society.

Notes from the Composers

Weak Chains — Jordyn Gallinek: The Staten Island Ferry is more about the experience — the wind, the view, the calm — than the destination. A single, weak chain is a last resort, holding a ferry to its dock. As the waters flood the terminal, the pressure between a rising boat and a drowning path will eventually cause that chain to snap. There’s a bitter irony in a ship gaining strength with rising water and no one being able to actually board.

Water Kiss — Marc Migó: This piece was commissioned by violinist Alice Ivy-Pemberton, to whom it is also dedicated. I drew inspiration from the terrible prediction of rising waters that will one day not too far in the future flood several parts of New York. I decided to write a piece that would shift between a sense of foreboding and a warm, nostalgic emotion. Therefore, I evoke both an apprehension for the future and a yearning for the past. My violin writing was also influenced by water movements, such as waves and currents.

Through What is no Longer — Iván Enrique Rodríguez: The theoretical physicist and cosmologist Lawrence M. Krauss once said: “People never ask what is the practical significance of a Mozart symphony or a Picasso painting [because] it’s part of what makes being human worth being human.” Through What is No Longer attempts to express the raw feeling and reaction when confronting the loss of those materials that were once deemed significant in our individual and collective life as a result of our societal negligence, greed, and lack of urgency when confronted with the current climate endangerment.

Murderers’ overFlow — Jonathan Cziner: Murderers’ overFlow pits the importance and danger of climate change with something seemingly lighthearted and trivial: the New York Yankees theme song. Millions of people make their way to Yankee Stadium each season to witness the winningest franchise in professional sports without realizing that that within the next 100 years the beloved stadium is projected to be at the edge of floodplains caused by rising sea levels.

Waterways — Sam Wu: The fish explore their new streets and avenues and boulevards, making their homes in corals growing out of skyscrapers.