The Coronavirus as Messenger

By Greta Gaard

On the day my university closed (March 13), the hope that Environmental Humanities scholars could do more than create another theory or proclamation responding to the present crisis arose in my bodymind and I began writing. Inspired by both the “World Scientists ‘ Warning of a Climate Emergency” and the “Call to Writers” issued by Kathleen Dean Moore and Scott Slovic, I was unsure what form the writing would take; I simply knew it needed to be part of the public humanities. The initial document was an essay, circulated among three close colleagues; two endorsed its immediate publication, and a third urged me to wait and see how this crisis would unfold before taking a stand. Three weeks later, on April 5, I revised the essay into an open letter and sent it to a small group of colleagues; again, some signed right away, while others suggested revisions, augmentations, resources. The document quickly became a collaboration which I was simply hosting.

As the letter circulated more widely, responses grew, and along with them, information about the pandemic’s unequal effects on diverse humans and the more-than-human world grew as well. Continuously, colleagues signed or pushed back with revisions that were incorporated to augment and transform the letter. Some colleagues quit temporarily, frustrated by the suggestions of other colleagues — and then they circled back with more revisions and caveats. Some colleagues never responded at all. Of these, those whom I considered friends as well I pursued with follow-up emails, seeking their views; again, some replied with edits and augmentations, others replied with flat refusals, some replied a month later in friendly notes that side-stepped the letter, and others kept silence. The entire process became an exercise in democratic discourse — and it is still in process, as more environmental humanities scholars are invited to sign on, and as information about the pandemic’s disparate effects on the world’s most marginalized humans and more-than-humans continues to emerge.

For academics it often seems easier to create a theory or issue a declaration than it is to align our behaviors with our theories. Instead of considering the ways to step back, even our profession tempts us to step up: write another article, create a special issue, host a conference, keep doing more of the same behaviors that distract us from the pandemic’s invitation to go home (if you have one), to stop moving (if you can), and see what arises. The indisputable fact that economic, political, and social structures need to change in order to create environmental health and climate justice does not dismiss the value of individual changes. Aligning the personal with the political, our individual actions can promote awareness, creating a community of support for stepping back from practices that enact overconsumption, deforestation, human oppressions and interspecies injustice.

Admittedly, it is risky to commit publicly to such behavioral changes because as humans we will sometimes fall short of our declared values — and then who will we be? How will we look to others? Our academic culture values effort only if it results in success. Our identities become attached to being right rather than being in-process.

I. Answering the Call

Epic world narratives tell sacred and secular stories about quests that heal wounded lands and seekers alike. In Celtic mythology it is the Fisher King; in Sumerian myth, it is Inanna. Osiris of Egypt, Odysseus of Greece, Jonah of the Hebrews. For Siddhartha of India, the Call arrives when the 29-year-old prince — restless with his life of elegance and debauchery — leaves the palace and encounters an old man, a sick person, and a corpse. Horrified that the outcome of all life will be old age, sickness and death, he is ready for the fourth heavenly messenger, a monastic, walking through the burial grounds. And Siddhartha commits to sitting with himself and watching the mind.

What if the coronavirus is a messenger, awakening humans to our material interbeing?

Perhaps the pandemic letter can function as a mindfulness practice, helping us notice the ways that stepping back from over-consumptive, anti-ecological behaviors are often conflated with “self-denial” — as if who we are is entangled with the behaviors of consumption and transport that contributed to the pandemic. If we eschew those behaviors, who will we be?

The European explorers, trappers, entrepreneurs and ministers who colonized North America clearly had a self-identity entangled with specific actions of consumption, transport, and entitlement. Their plunder of wildness enacted through the trapping, hunting, slaughter and skinning of native animals (deer, beaver, fox) was a colonial enterprise that included indigenous and enslaved humans in its exploitations and appropriations, confirming a linguistic, cultural, and ideological symmetry between “the fur trade” and “the slave trade” — economic operations that created profit through theft of life, labor, and land.

In North America today, it is easy to recognize parallels between the coronavirus pandemic and the pandemic of colonialism that decimated indigenous communities, deforested entire regions, pushed alcohol consumption, provided blankets with smallpox virus, entwined conquest with sexual violence against women and children, shot wolves and bison to near-extinction, and extracted oil, uranium and coal from native lands while “relocating” indigenous survivors to underfunded “reservations.” The “uniqueness” of COVID-19 is not so unique to native nations, who are already sorely underfunded in health care, and now more heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

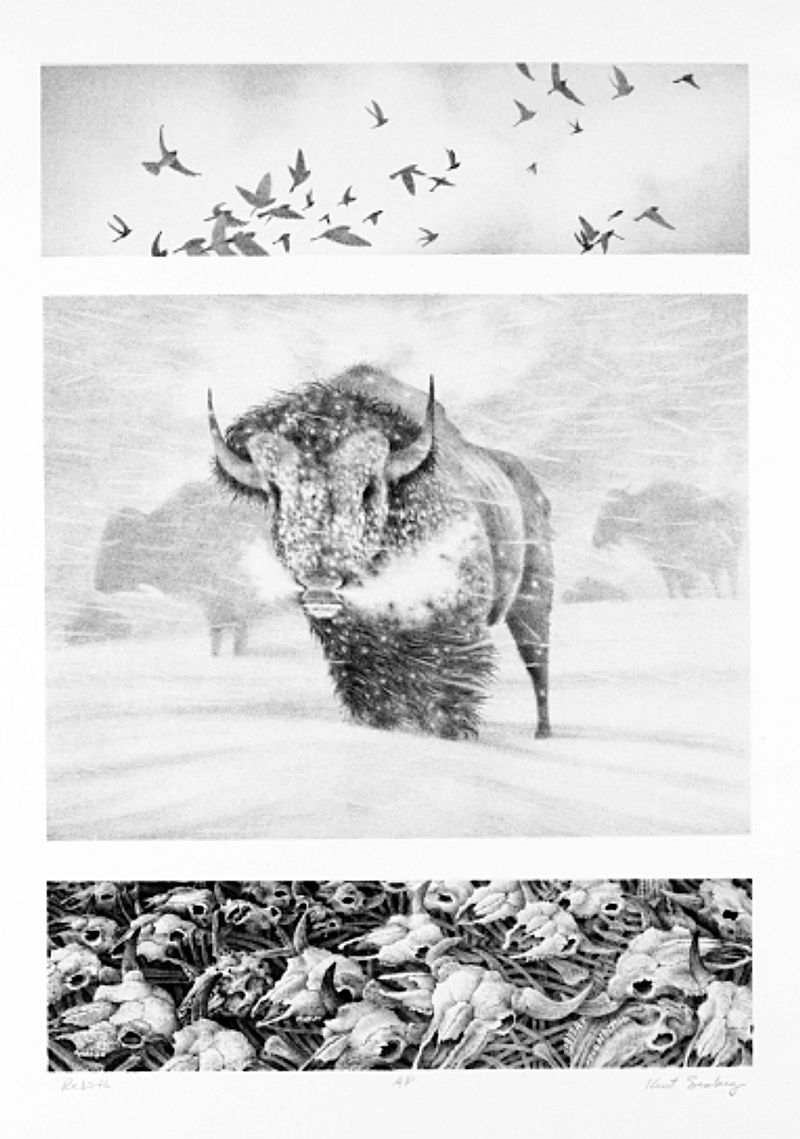

As Sami-American artist Kurt Seaberg observes, colonialism recognized the interdependence of indigenous tribes and indigenous species, targeting one to annihilate the other: in this process, the North American bison was one of a handful of species targeted intentionally for extinction in a military campaign to subdue Native American resistance.

In Seaburg’s lithograph “Rebirth” (2005), a triptych represents the interbeing of past, present, and future through the millions of bison skulls retrieved and photographed in piles stacked two-stories high, a murderous metonymy representing the Nineteenth century men who rode trains across the Great Plains and shot bison for sport. The birds taking flight above variously represent the companion spirits of bison and indigenous communities, soaring in the rebirth of a just and sustainable future. In the present moment at the center, the bison looks directly at the viewer — for breathing takes place only in the present, a reminder that only in the present might we breathe — and possibly be infected by the coronavirus. Or, we can breathe in the awareness of our interbeing, and align our behaviors accordingly.

II. Sustainable Happiness and the Dharma

Like most environmental humanities educators, I continually seek ways to infuse ecocritical themes into my foundations courses. In 2019-20, I have been teaching a second-year writing course weaving together themes of climate change, species extinction, the rigged economy, and happiness studies, calling it “Sustainable Happiness.” Thanks to ecocritical Affect Studies scholarship by Sarah J. Ray, Kyle Bladow and Jennifer Ladino, we know that bad news about climate change (not to mention pandemics) doesn’t motivate or empower readers; rather this dire information creates a state of overwhelming debilitation and numbing. With happiness studies, I’m able to invite students to explore questions like What views of happiness got us into this mess? What views of happiness can get us out?

By the second of four essays, students are making the connections: overhunted and dying-out species, clearcut forests and polluted waters, fossil fuel industries and animal agribusiness may provide temporary happiness (and wealth) for economically elite humans, but the loss of so many animal species, the health and happiness costs to laboring humans, and the ecosystem effects of polluted environments will last far longer. To buffer this bleak realization, we draw on the positive psychology of Sonja Lyubomirsky in The How of Happiness, learning that while 50% of our happiness is genetically predetermined, only 10% is due to life circumstances, and up to 40% is the result of personal behaviors and views. Coupled with Buddhist monk Mathieu Ricard’s Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill, I weave together Buddhism’s ten Paramis (perfections of the heart) with Lyubomirsky’s happiness practices to create a series of twelve practices students can undertake. While the Fall 2019 semester confirmed these practices provide students with skills for cultivating the resilience needed to engage with the facts of economic and environmental crises, when our campus went completely online at mid-semester in Spring 2020, my writing students continued their happiness practices to buoy them in facing the linked pandemics of climate change and COVID-19.

The “stealth” teaching within these happiness practices is variously called the wisdom of not-self (anatta) in Buddhism, or transcorporeality in material feminism. Happiness practices of interbeing begin with gratitude — the acknowledgement and appreciation that our lives wholly depend on the generosity of humanimals across class, age, gender, ability, and nation as well as on benevolent vibrant matters such as plants and insects, soil and sunlight, water and air. Given that our survival and well-being co-arise with material, energetic, and social forces that make and remake our lives, we can ask Is happiness an individual project? A socioeconomic project? An interspecies and ecological project? Or is it all-of-the-above?

III. Queering The Boon of Interbeing

In Christina Rosetti’s pre-Raphaelite poem “Goblin Market” (1862), sisters Lizzie and Laura go to the brook each evening to collect water, and that’s where they hear the goblins cry “Come buy our orchard fruits / Come buy, come buy…”. “Curious Lizzie” chooses to linger one evening and buys the fruits “with a golden curl” from these transspecies goblin men, “leering” and “sly,” their animal natures lascivious and seductive. But after gorging herself on their delicious fruits, Laura never sees the goblins again, and “dwindles,” becoming pale and thin with yearning. To save her sister, Lizzie risks everything and goes to the brook to provoke the goblins, offering to buy their fruits for take-out. Enraged, the goblins attack her, smearing “juice that syruped all her face” before vanishing into the woods, leaving not one fruit behind. Rejoicing with “inward laughter,” Lizzie returns to Laura and offers her fruit-smeared body for savoring. While the poem’s morality tale of “forbidden fruits” has been thoroughly explored in literary criticism, from a mindful ecocriticism standpoint, savory fruits and seductive transmen aren’t the real problem: it’s craving. The insatiability of craving, or tanha (“thirst”), is what leads to suffering, but when the sweet and bitter fruits of life are experienced without clinging, without pushing them away or expecting them to be permanent, craving is not merely appeased, but extinguished.

Recognizing that experiences of happiness as acquisition, wealth, power, fame, achievement, sensory gratification, consumption and travel ultimately fail to dislodge the persistently unsatisfying quality of the human condition because the happiness they provide is limited and temporary, seekers answer the Call and commit to the search for lasting happiness. Leaving behind old patterns and habits, seekers learn to see life in a new way, gain insight into interbeing (anatta), and release the illusion of a separate self. Of course, the purpose of the quest is not for the individual alone, but for the community: insight must be shared in order to transform our relations with the more-than-human world. Where should we begin?

If your starting point isn’t ideal, then “start where you are,” urge educators from agricultural innovator George Washington Carver to Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron — but don’t stop there; keep going, until the effort and attention and interactions you cultivate benefit all beings.

Both Carver and Chodron locate their identities in larger communities: for Carver it was the black sharecroppers who needed a way out of wage slavery, and who benefited from the peanuts and sweet potatoes Carver’s research confirmed would nourish both the cotton-exhausted soil and the black farmers alike. For Chodron and other western Buddhists, the inter-identity of anatta articulates the understanding that autonomous individualism is an illusory concept in an interdependent, co-arising world.

In “Towards a Queer Dharmology of Sex,” Roger Corless (2004) reconceives central Buddhist concepts of dependent origination, emptiness, and Buddha-nature as intrinsically queer because they undo dualistic ways of thinking and replace them with non-dual forms of consciousness. Notably, the concept of anatta (no-self) resists essentialism by defining human identity in terms of constantly-changing impermanence and interbeing — in effect, anatta queers identity.

From texts such as Cate Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson’s Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire (2010) to Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle’s Goodbye Gauley Mountain (2013), queer ecology has both critiqued heteronormativity for its anti-ecological mandates and explored queer natures across species, genders, and sexual behaviors. Annie Sprinkle defines ecosexuality as “a way to create a more connected relationship” with earth. “We like to have skygasms,” says Sprinkle. “Beth and I have intercourse with the air that we breathe.” As a way of performing, renewing, and eroticizing people’s material connections with earthOthers, Stephens and Sprinkle conduct ecosexual polyamorous and posthumanist weddings. Their EcoSex Manifesto 3.0 (COVID-19 edit) reconnects human eros with more-than-human natures.

So, what if the coronavirus isn’t merely a messenger? What if it’s the Officiant in an ecosexual multispecies commitment ceremony? It would ask all of us seekers, Have you discovered that your own lasting happiness and well-being are deeply intertwined with the health and happiness of all species, including your own? Do you now pledge to love, honor, and cherish the health and happiness of this earth and all earthOthers until death brings us closer forever?

If so, let’s breathe together (with masks).