Mountain women bear the brunt of climate change

Women, who do the majority of drudge work in the economically and environmentally fragile Hindu Kush Himalayas region are disproportionately impacted by the effects of climate change.

It is widely recognised that climate change effects take the heaviest toll on the vulnerable and the poor. These impacts are exacerbated if the affected person is a woman.

A recent study by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) sheds light on the disproportionate levels of adversities women and girls face due to climate change, especially in the economically and environmentally fragile region of the Hindu Kush Himalayas.

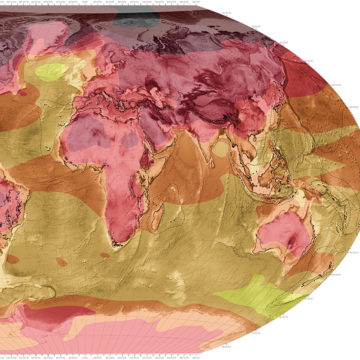

The region extends 3,500 kilometres m from Afghanistan in the west to Myanmar in the east, stretching across eight countries with varied political and economic systems. Despite its rich biodiversity, the region is home to the world’s poorest, and those most vulnerable to climatic change impacts. Women in this region already struggle under the burden of gender-biased attitudes, unequal power relations and division of labour, and limited land ownership and control. Additional adversities only add to their problems.

“Climate change will have differential impacts among countries and those living in poor countries are likely to suffer disproportionately, both in terms of being impacted earlier and to a greater degree. The Hindukush Himalayas (HKH) region is one of these,” the study notes.

Due to geographical isolation, poor physical and economic infrastructure, and poor access to markets and technologies, the communities face many types of poverty; low income, ill health, poor access to health facilities, malnutrition, poor education, and a high dependence on the natural environment.

Mountain residents have always been exposed to droughts, floods, soil erosion and changes in the crop cycle. The difference now is that the intensity and frequency of such events have increased over recent decades, while the socioeconomic drivers of change – such as migration, urbanisation, increasing demands for energy and power, the extraction of water for industry and agriculture, waste dumping, and water and air pollution – also add to the pressure. These have weakened the ability of the communities to adapt.

Women more at risk

Gender structures and deeply entrenched socio-cultural ideologies that marginalise women’s work make women more vulnerable than men. Mountain women, who have great a resilience and the knowledge to adapt to various stresses, are often left out of key decision-making processes and are marginalised further, even though they are likely to suffer more in the future. Climate change is bound to increase these gender inequalities further in many ways.

One form of so-called gendered vulnerability to climate change relates to the highly skewed division of labour in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region. The high rate of male migration out of the mountains results means women must perform most of the agricultural and pastoral work, in addition to their responsibilities for household work and casual labour.

The paper also reveals that in some mountain regions in India, women undertake 4.6 to 5.7 times more agricultural work than men. In Nepal, the range is skewed even more with women carrying out 6.3 to 6.6 times the agricultural work that is done by men.

Increased drudgery

Women who are often in charge of procuring natural resources for the family find themselves walking greater distances to collect water, fuel, food and medicinal plants as production schedules are affected by changing climate conditions. This, in turn, increases their workload and drudgery.

A women’s role is intrinsically tied to the collection, storage and management of water and women pay the biggest price when it comes to poor quality and lack of access to water. Any increase in water scarcity means that women and girls must spend more time on this task, which often means that girls do not have time to attend school. And if the water quality worsens, women and girls are the first to be exposed to waterborne diseases.

During extreme events such as droughts and floods, women and girls face the additional risks of gender-based violence, sexual harassment, trafficking and rape. In Nepal, an estimated 12,000 – 20,000 women and children, including some boys, are pushed into forced labour and sex work every year. The data suggests that trafficking increases by 20-30% during disasters.

At such a time, women and girls are also more prone to mortality. In Nepal, flood-related fatalities were found to be significantly higher according to gender and age. In Bangladesh, mortality levels were found to be higher for women above the age of 10 — three times higher than those of males — in the 1991 cyclone and flood.

The common reasons for this are that early warning signs are often primarily disseminated in public places, to which many women don’t have easy access. Due to restrictive cultural norms, some women in Bangladesh couldn’t evacuate on time as they were not allowed to leave the house without a male relative, losing precious time that could have saved their lives. Due to ideologies that present women as a symbol of self-sacrifice, it is women who typically eat the leftover food when food becomes scarce, compromising their health and nutrition.

Leadership roles

The report gives examples of where women can play a leadership role in adaptation strategies, such as the diversification of crops in Nepal, where women promote homestead gardens and water ponds, and in Sikkim in north-east India where women have begun to domesticate wild cardamom which is more disease resistant.

This higher vulnerability of women to climatic stresses doesn’t mean that males are not badly affected, however. Much depends on one’s position in the society often related to a complex caste system and economic status. “There is a paucity of documentation on the specific risks and vulnerabilities, along with coping strategies in the context of climate change of mountain communities generally and from a gendered perspective particularly,” the study said.

The study, which aims to help understand women’s resilience to climate change impacts, stresses the need to place women at the centre of climate adaptation policies and to initiate climate financing mechanisms to support gender-sensitive and responsive innovations.