A Plague Genealogy

By Laura Wright

The flu pandemic of 1918 killed around one percent of the world’s population. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over the course of its spread during 1918 and 1919, “it is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.” By December of 1918, in Asheville, North Carolina, where I live, the Citizen-Times reported that there had been nearly 5000 cases regionally with 138 deaths; at the time, the total for the state of North Carolina was around 14,000. News stories from earlier in the year point to a slow response to the outbreak, noting that October 15 “was the first time that Ashevilleians have appeared generally with the white mouth and nose coverings.” By that evening, however, “The sight had lost its novelty. Wearers are expected to multiply now that the ice has been broken.”

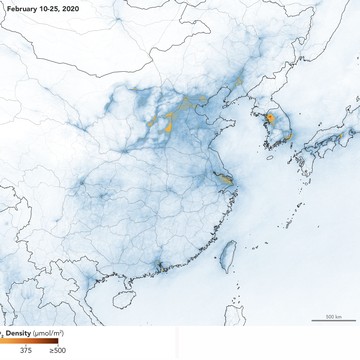

The 1918 flu was avian in origin. COVID-19, the pandemic that is currently racing around the planet, likely emerged from pangolins in a live animal market in Wuhan, China, but as Thom Van Dooren notes, if the pangolin “does turn out to be the unwitting and unwilling culprit behind this pandemic, this unlucky animal will join a long list of others whose life was cut short, whose species was endangered, and whose environment was destroyed, by a diverse range of ongoing human activities that are simultaneously helping to engineer new zoonotic diseases.” With attention to our Open Letter’s recognition of the fact that in the moment “a virus carries the message of our interbeing — across bodies, species, continents,” I offer a nonlinear plague genealogy situated within fiction and history in order to probe the social, environmental, and economic interconnections that underscore and complicate this Anthropocenic crisis.

***

I think about pandemics and plagues quite a bit, even prior to this most recent one; I teach environmental literature, so they show up in much of what I read and teach. I regularly teach Margaret Atwood’s 2003 work of speculative fiction Oryx and Crake, a novel set in a near possible and dystopian future. The narrative toggles back and forth between the time before and the aftermath of a man-made virus unleashed on humanity in order to wipe us out and start over with a more humane, environmentally friendly, vegan version of our species. The goal of Crake, the “mad” scientist who creates the plague, is to “break the link in time between one generation and the next, . . . [so that] it’s game over forever” (223). This problematic scenario is the paradox that Atwood’s novel engages, the utopian desire to erase all of humanity’s ills and start fresh and from an ideally better place that, if it happens at all, necessarily results from dystopian — and genocidal — social destruction. Atwood’s novel also shows that we are always so much ourselves, a species that has evolved to repeat its previous mistakes. Evolution as devolution: Crake’s genetically modified perfect species, the so-called Crakers, start turning into imperfect humans the minute he’s gone. His failing is that he can’t eliminate the human capacity for imagination, story-telling, and art, and, ironically, those are the things that both make us wonderful and get us into trouble. If Atwood’s fictional prediction is to be understood — and if the history of our species is to serve as evidence — we seem hardwired to always be both our best and our worst selves, creators and annihilators in equal measure. Plagues often bring this reality into stark focus.

Back in the real world, COVID-19 is exposing the fault lines in our culture; for example, the CDC reports that despite the fact that only 13 percent of the U.S. population is African American, African Americans account for 34 percent of COVID-19 deaths nationwide. Immigrants in detention centers, inmates in prisons, the elderly in nursing facilities are all at increased risk due to their confinement. Food insecurity is exacerbated for children whose main source of nutrition comes from schools that are now shuttered — and children and women who are victims of domestic violence now find themselves, in many cases, trapped at home with their abusers. And then, at the end of April 2020, Donald Trump invoked the Defense Production Act to force meat packing plants and slaughterhouses to maintain production — even as these places are hot zones for COVID-19; thousands of workers in plants across the nation have fallen ill with dozens dying.

The labor force in meat processing facilities, predominantly Latino, African American, and immigrant, tends to be made up of some of the most vulnerable members of American society. According to Samantha Gillison, conditions in meat processing facilities are horrific, crowded, poorly ventilated, and unsafe. She notes that “in 2018, OSHA records revealed that, for the previous two years, U.S. workers at meat processing plants had suffered an average of two amputations a week (which included the loss of an eye) after suffering severe injuries on the line.” The Trump administration’s mandate that meat packing plants remain open is indicative of a mentality that views the laborers in those places as disposable, even as it is couched in the rhetoric of critical infrastructure, maintenance of the food supply chain, and support for “opening” a devastated economy.

But throwing red meat to his base — animal bodies offered on the altar of sacrificial meat packers — is a token act, unlikely to assuage the global recession in which we find ourselves. At present, economists are predicting a market contraction on par with the Great Depression. According to Nan K. Chase, in Asheville during the Great Depression, “suddenly there was no work, no money circulating. . . . Commerce became a degrading patchwork of odd jobs, welfare, and luck.” My father’s father lost everything and had to go to work on a logging crew, working for the timber industry, clear-cutting the mountains where he lived, making, I’m told, about a dollar a day. Like the work that takes place in meat processing plants, the work my grandfather was forced to do was incredibly dangerous, and the Great Depression created an exploitable workforce that — again, like meat processors — labored under deplorable conditions in an industry that devastated the environment. According to Becky Johnson, “the moneyed timber moguls from the North descend upon Appalachia, exploiting its massive forests and impoverished people for their own profit, destroying the landscape and exacting a human toll as well.”

Ron Rash’s novel Serena is about this dynamic in its exploration of the timber industry in western North Carolina during the Great Depression and characterizes the treatment of the loggers as imminently disposable during a time when people were desperate for jobs and forced to destroy the landscape they loved, on which they also depended, in order to feed their families. The narrator notes, “as the crews moved forward, they left behind an ever-widening wasteland of stumps and slash, brown clogged creeks awash with dead trout” (116). Like Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, Rash’s novel is also about an apocalypse: after they’ve cut the last tree, one character notes, “‘I think this is what the end of the world will be like” (336). In 2020, even as the trees have now grown back, the old logging roads are still visible and walkable throughout the mountains, testaments to a legacy of greed and environmental destruction.

Even as Asheville residents were fighting for their survival during the Great Depression, the wealthy were orchestrating the 1934 establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Again, we seem hardwired to always be both our best and our worst selves, creators and annihilators in equal measure. According to Carlos C. Campbell, the “creation of the 18 national parks prior to 1924 had been accomplished by the setting aside of lands which already belonged to the federal government. Not so with the Great Smokies. The 515,225.8 acres constituting this park were then in private ownership, in more than 6,600 separate tracts” (12). A whopping 85 percent of that land was owned by timber companies, with 1200 tracts being privately owned farms. In the battle between the timber industry and the advocates for scenic beauty, farmers already hurting from the impact of the Great Depression were forced off their land, which was condemned. Today, the park is home to an abundance of wildlife and plant species and sees millions of visitors each year.

***

A plague, an economic depression, the annihilation of a forest by men desperate for work, the creation of a national park from land effectively stolen from poor farmers. This sequence of events forms a kind of genealogy implicated in an interspecies interaction that saw a virus jump from one to another, part of an unfolding chronology of events that witnessed the establishment of a space in which various species are now protected and others have been ejected. That enabled men, like my grandfather, who loved and depended upon the land and its waterways to decimate and pollute them as a means of their own survival in the interest of timber barons. A park as the means to save the forest even as it displaced and exploited its people. As one of the loggers in Rash’s novel notes, “running folks out so they can run the critters in . . . [is] a hell of a thing” (335).

***

This legacy of species displacement, economic exploitation of the labor of loggers, and subsequent environmental devastation that makes up the fabric and the fallout of the 1918 flu pandemic can show us much about the present circumstances of the current crisis. And in both cases, then, as now, there are the animals. The ones we choose to protect and the ones industrialized cultures choose to process via the machinations of factory farming at the insistence of big agriculture. While president Trump early on called it the Chinese virus, it’s worth remembering that H1N1, the “Swine flu,” originated in the U.S. in 2009 after it jumped from pigs to humans. Such viruses jump from animal to human not based on a specific demographic but rather on the human species’ more general insistence upon ingesting nonhuman animals. The animals sold in the “wet markets” in China are caged and terrified, their deaths horrific. But the bodies of animals sold in supermarkets across the U.S. suffered as horrifically prior to being turned into the “meat” that U.S. consumers seem to be incapable of living without. And while there has been worldwide outcry, much of which has come from the U.S., to shut down China’s wet markets, there seems to be no such outrage over what we do to animals in the West — until there are suddenly articles in places like The Guardian discussing the horrific methods being employed in the culling of “livestock” in the U.S. due to the fact that our food system is “choking” under the weight of the pandemic.

There are genealogical lessons about the connectivity and interdependence of land, species, disease, and labor that one can learn from this particular plague in order for our species not to be completely wiped out the next pandemic around. One has to do with how we think about what we eat. As Deane Curtin notes, “as a ‘contextual moral vegetarian,’ I cannot refer to an absolute moral rule that prohibits meat eating under all circumstances. There may be some contexts in which another response is appropriate,” but “if there is any context . . . in which moral vegetarianism is completely compelling as an expression of an ecological ethic of care, it is for economically well-off persons in technologically advanced countries.” I would argue that those of us who find ourselves within the context Curtin describes — “economically well-off persons in technologically advanced nations” — need to stop eating animals and stop destroying their habitats. Further, we need to feel compassion for them and for our fellow humans, even after the narratives of the various horrors inflicted on them cease to take up space in our daily lives — after things return to “normal,” whatever that might mean. Even as I write this piece, in resonse to the pandemic, Jonathan Safran Foer has published an essay in the New York Times calling for an end to meat eating, couching his argument in the most ecofeminist terms possible by highlighting these same interconnections — between the exploitation of non-human species, racial injustice, and climate change.

Incomprehensibly, as the death toll in the U.S. is the highest of anywhere on the planet, people are protesting in nearby Waynesville, driving through grocery store parking lots in cars and trucks flying American flags, their vehicles covered in painted messages like “open NC!” and “our children are being held hostage!” We are, once again, at the edge of a precipice of our own making. Everything is precarious and uncertain, and we are all unwitting victims in an uncontrolled experiment, like the one Atwood explores in Oryx and Crake — and one that will require many of the most vulnerable of our species to choose between impossible and unconscionable options, like my grandfather and the fictional loggers in Rash’s Serena. Since we keep killing them, eating them, decimating their habitats, I have always hoped that the nonhuman animals that are endlessly at our mercy might teach us a lesson — and every so often, it seems, they try to teach us. History has shown us this story before, and maybe this time we should listen.