Respecting Children, Respecting Species

Writing in May 2020, still deep in coronavirus lockdown, I wonder about all the parent-child conversations that have taken place during the last months. Within this international chatter I think about the diversity of emotion, the extent of fear and confusion from both adults and children alike, and the attempt to translate complex science and unsettling mortality into more palatable language. I also wonder about the abrupt changes to everyday life that many people are perhaps adapting to better than they might have imagined.

Lockdown affords us a vantage point on “normality,” what our society takes for granted regarding its shared set of social norms. Furthermore, lockdown, because it necessitates changes to our everyday practices, also affords insight into social change. “Normality” might be exposed either as absurd (the high pace of life) or even as deadly (excessive car use). Though our main priority is trying not to catch the virus and spread it, this time is also an unexpected social experiment in which life priorities are open to re-assessment and social norms might come more into explicit focus and fall under critical scrutiny. Of course, it is during childhood that society enrols us into its various narratives of right and wrong, and social norms begin to structure how we see the world, and how we see our place in the rest of nature.

With a focus on childhood there are at least two traps to avoid. Firstly, as Nick Lee argues in Childhood and biopolitics : climate change, life processes and human futures, childhood studies cautions against objectifying children as human futures to the detriment of seeing them already as social, agential, and political citizens. Notably childhood studies and animal studies share the interest in returning a sense of agency to the socially marginalised. The second trap is not wholly distinct from the ‘children as human futures’ discourse but is more specifically related to Lee Edelman’s (in No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive) critique of ‘reproductive futurism’, the idea that ethico-political projects are often couched in terms of fighting for a better future for children. This does two problematic things. Firstly, it potentially normalises a heteronormative notion of kinship and marginalises people who do not wish to conform to that idea. Secondly, it embeds a human-centred, or ‘anthropocentric’ rationale, marginalising other kinship relations, such as those we have with other species or those which take place between other species. Ultimately it may exclude the idea that we may also want to safeguard the flourishing of the more-than-human.

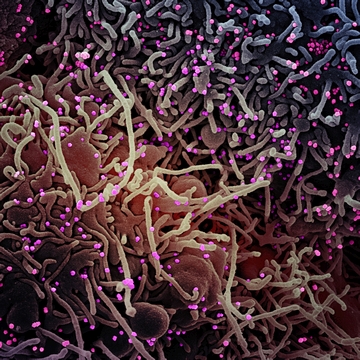

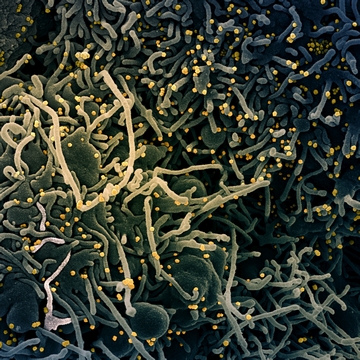

The idea that the flourishing of other species is important, and that it is significantly linked to that of human health is absent from much of the current debate on the pandemic. It is noticeable that barely any politicians are talking about the role that habitat destruction and the practice of turning animals into commodities have played in the pandemic even though there have now been numerous high-profile thought pieces (e.g. a recent essay by Sonia Shah in The Nation) that have examined just that point. What becomes dominant as the origin story of the coronavirus? I wonder how many parents have introduced this dimension of coronavirus causality into their conversations with their children. Would that be too much complexity? Presumably, curious children are asking why this pandemic has happened. It could be a mistake to always assume that because a topic is complex children ought to be shielded from it. Indeed, it could instead be reframed as an educational opportunity so that children become better able to make links between human economic practices directed toward ecosystems and animals, and the rebound effects they can have for human health.

Everyday practices that “turn animals into commodities” and instances of “habitat destruction” are exactly examples of routinised actions that we come to think of as ‘normal’ during our childhoods, not explicitly of course, but as taken-for-granted aspects of the food that most of us consume and the economic development that we indirectly endorse. Implicitly we learn that we have privileged the human above other animals. While these practices are part of the causality of the pandemic, they are also equally part of the causality of the climate crisis. This far larger crisis has special resonance for children today by virtue of their inevitably inheriting the inaction of adults, as we move deeper into this century. Much has been written about the ethical duties we have toward children and future generations in this respect, as well as the inadequacies of climate and environmental education in our schools which might work against children becoming agents of change for less human-centred and more ecocentric and just societies. Even though multiple nations agreed to include environment and development education as a cross-cutting theme in education as far back as the 1992 Rio Earth Summit the reality has been that it has taken Greta Thunberg’s climate strike movement to bring into relief the marginalisation of these topics.

This brings us back to thinking about those parent-child conversations. Familial tensions around food are not new (see G. Gaard 2010 and L. Wright 2013). Today we surround childhood with animal representations, in toys and on the screen. Social norms which construct both children and animals as innocent and pure reinforce each other and promote the idea that we view childhood as a protected space. However, a key disruption to this narrative occurs when children inevitably realise that our society kills animals on an enormous scale. How do parents broach that subject? How do parents negotiate those awkward feelings that children may provoke in their curiosity? How does normalised violence become part of the everyday life of families? And how do parents talk to their children about the climate crisis, of which this enormous level of violence against animals is a contributing factor? Parental responses here can vary widely according to the power relationships within families. Some parents can be accommodating to children who wish to cease their consumption of animals and certainly there is some evidence for a cultural shift in the status of children and their choices when it comes to food (see R. O’Connell and J. Brannen, in Childhood, 2014).

Communicating honestly and well is undoubtedly part of the best strategy for parents. This might mean moving beyond one of our central social norms of childhood as a protected space. Instead childhood also needs to be a time in which children can develop curiosity and critical thinking about the world they are getting to know. That means empowering children with knowledge even if it is messy, contradictory, and potentially unsettling. Whilst the cultural championing of empowered children taking a stand against the climate crisis may problematically extend the cultural trope which associates children and nature with goodness and innocence (see Gene Myers, The Significance of Children and Animals), it is nevertheless also an important democratising development which bolsters children’s rights, agency and voice. Moreover, we would do well as a society to reverse the assumption of one-way learning. If children, less compliant to social norms, question things, in this case question the eating of animals, a moment for adult learning and reflection may also take shape. And if, as we have seen, the commodification of animals is bound up in the great crises of our times, then maybe our lockdown lesson should be that facilitating children’s critical thinking on this matter is one of the most important responsibilities we have toward children and future generations of all species, even if that calls into question much of what we have taken for granted.