The UN is slowly warming to the task of protecting World Heritage sites from climate change

UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee has issued its strongest decision yet about climate change, acknowledging the worldwide threat posed to many World Heritage properties. The decision, adopted at the completion of the Committee’s annual meeting in July 2017 in Krakow, Poland, “expresses its utmost concern regarding the reported serious impacts from coral bleaching that have affected World Heritage properties in 2016-17 and that the majority of World Heritage coral reefs are expected to be seriously impacted by climate change”.

It also urges the 193 signatory nations to the World Heritage Convention to undertake actions to address climate change under the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global average temperature increase to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial temperatures. This decision marks an important shift in the level of recognition by the Committee tasked with protecting World Heritage properties, apparently jolted by the devastating bleaching suffered by the majority of World Heritage coral reefs around the world.

In the past, the Committee has restricted its decisions to addressing localised threats such as water pollution and overfishing, choosing to leave the responsibility to address global climate change to other parts of the United Nations. In the preamble to its latest decision, the Committee has recognised that local efforts alone are “no longer sufficient” to save the world’s threatened coral reefs. But while this is an encouraging progression, some members of the Committee are still struggling to come to terms with addressing the global impacts of climate change. This is despite the impacts becoming more pronounced on other World Heritage properties, including glaciers, rainforests, oceanic islands, and sites showing the loss of key species.

The ‘jewels’ of marine world heritage

In June 2017, UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre released the first global scientific assessment of the impact of climate change on all 29 World Heritage-listed coral reefs that are “the jewels in the World Heritage crown”.

The report paints a dire picture, with all but three World Heritage coral reefs exhibiting bleaching over the past three years. Iconic sites like the Great Barrier Reef (Australia), the Northwest Hawaiian islands (United States), the Lagoons of New Caledonia (France), and Aldabra Atoll (Seychelles) have all suffered their worst bleaching on record. The most widely reported damage was the unprecedented bleaching suffered by the Great Barrier Reef in 2016-17, which killed around 50% of its corals.

The scientific report predicts that without large reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, all 29 reefs will “cease to exist as functioning coral reef ecosystems by the end of this century”. Reefs can take 10-20 years to recover from bleaching. If our current emissions trajectory continues, within the next two decades, 25 out of the 29 World Heritage reefs will suffer severe heat stress twice a decade. This effectively means they will be unable to recover.

It should also be noted that the majority of World Heritage coral reefs are far better managed than other reefs around the world, so the implications of climate change for coral reefs globally are much worse.

All coral reefs are important

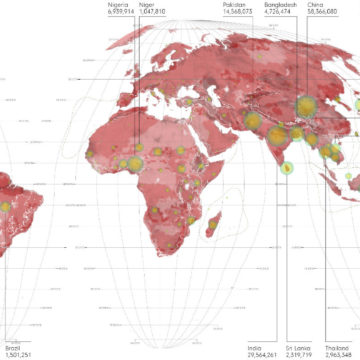

Almost one-third of the world’s marine fish species rely on coral reefs for some part of their life cycle. There are also 6 million people who fish on reefs in 99 countries and territories worldwide. This equates to about a quarter of the world’s small-scale fishers relying directly on coral reefs.

Half of all coral reef fishers globally are in Southeast Asia, and the western Pacific Island nations also have high proportions of reef fishers within their populations. In total, more than 400 million people in the poorest developing countries worldwide live within 100km of coral reefs. The majority of them depend directly on reefs for their food and livelihoods.

Coral reefs provide more value than any other ecosystem on Earth. They protect coastal communities from flooding and erosion, sustain fishing and tourism businesses, and host a stunning array of marine life. Their social, cultural and economic value has been estimated at US$1 trillion globally. Recent projections indicate that climate-related loss of reef ecosystem services will total more than US$500 billion per year by 2100. The greatest impacts will be felt by the millions of people whose livelihoods depend on reefs.

Where else?

Recognising that the majority of the World Heritage coral reefs are expected to be seriously impacted by climate change is a good start. However, the Committee cannot afford to wait until similar levels of adverse impacts are evident at other natural and cultural heritage sites across the world.

The World Heritage Committee and other influential bodies must continue to acknowledge that climate change has already affected a wide range of World Heritage values through climate-related impacts such as species migrations, loss of biodiversity, glacial melting, sea-level rise, increases in extreme weather events, greater frequency of wildfires, and increased coastal erosion. To help understand the magnitude of the problem, the Committee has asked the World Heritage Centre and the international advisory bodies “to further study the current and potential impacts of climate change on World Heritage properties”, and report back in 2018.

Two of the key foundations of the World Heritage Convention are to protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage, and to pass that heritage on to future generations. For our sake, and the sake of future generations, let’s hope we can do both.

ADDENDUM:

The Australian government requested that UNESCO remove a case study on the Great Barrier Reef from the final report. In response, The Union of Concerned Scientists published an updated version of the case study at the same time the report was released. For more, please see lead author Adam Markham’s statement on the Australian government’s intervention.