Greening our Planetary Menu

Bifrost / Green My Favela / HfE Circumpolar Observatory

The agricultural sector encompasses a multitude of environmental problems. Avoiding meat and dairy is the most effective way humans can reduce our carbon footprints on the earth. The global loss of wilderness areas to agriculture is the primary cause of the sixth mass extinction that we are currently experiencing. Giving up beef in human diets worldwide would reduce the world’s carbon footprint more than fossil-fuel dependent forms of transportation. Beef produces up to 105 kg of greenhouse gases (GHG) per 100g of meat (tofu produces >3.5kg). Freshwater fish farming is also a heavy methane producer, providing two-thirds of fish stocks in Asia and 96% in Europe.

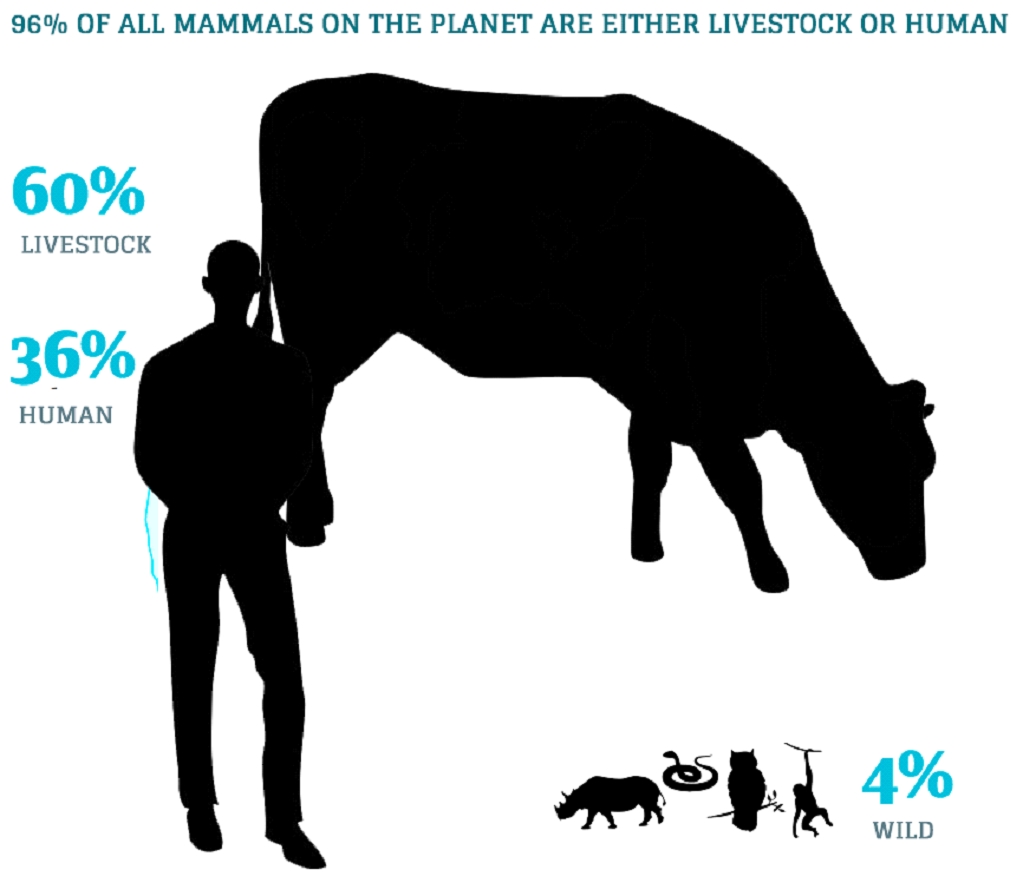

40,000 farms in 119 countries produce 40 food products that represent 90% of all the food consumed globally. Even the lowest-impact beef is responsible for six-fold more greenhouse gases and uses 36 times more land than producing plant protein such as peas. From farm to table, the impacts on land use, climate change emissions, freshwater use, eutrophication and acidification are immense. 86% of all land mammals are now either livestock or human. $500 billion is spent every year on agricultural subsidies.

To avoid dangerous climate change, our methods of food production that directly and indirectly yield high greenhouse gas emissions, due to the methane produced by animals but also via deforestation and carbon sink disturbances, must shift dramatically. Additional risks to water security from farming and the production of ocean dead zones from agricultural pollution (most notably in Florida’s red tide catastrophes), the environmental health risks associated with the overuse of pesticides, the long-haul transportation of food and livestock feed, and the mega-farming culture that leaves us vulnerable to systems collapse are but a few of the risks we must imminently tackle. The estimated 2.3 billion increase in the world’s population by 2050, combined with rising global incomes that are enabling more people to eat meat-rich western diets, is mounting to a perfect storm that will collide with critical environmental limits beyond which humanity will be unable to cope.

If the most harmful half of meat and dairy production was replaced by plant-based food, it would still deliver about two-thirds of the benefits of getting rid of all meat and dairy production. Without meat and dairy consumption, agriculture’s greenhouse gasses (GHGs) could be reduced by 60% and farmland use could be reduced by more than 75%—a combined area equivalent in size to the US, the EU, China and Australia—and still provide enough to feed the world.

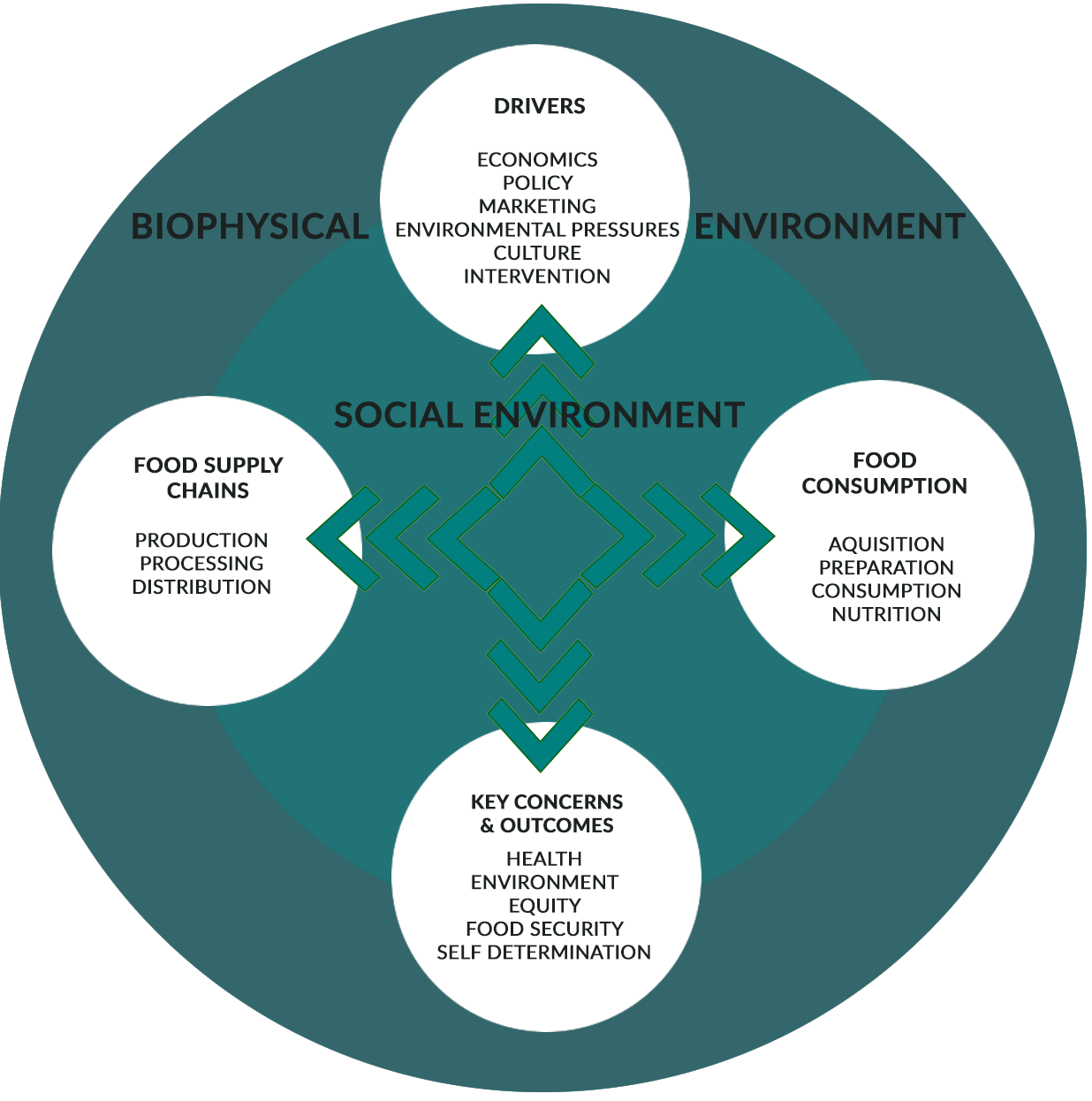

Improving how products are labelled for the consumer, educating the public sector about the impacts of consuming meat, educating about farming practices and supply chains (and legislating for supply chain transparency), introducing subsidies for sustainable and healthy foods, and eliminating subsidies for meat and dairy and taxing them instead are all necessary steps in the process of reordering our agricultural supply chains.

The latest IPCC report gives us about a decade to control global warming to keep the planet under an already deeply problematic 1.5°C warming scenario. A global shift to a flexitarian diet diet—meaning the average person must eat 75% less beef, 90% less pork, and halve their intake of eggs, while tripling consumption of beans and pulses and increasing their consumption of nuts and seeds four-fold—is necessary to keep us under a 2° warming scenario. In wealthier nations, the required dietary changes are even more drastic—people need to cut beef by 90% and milk by 60%, while increasing beans and pulses (fruit or seed of a legume) between four- and six-fold.

Just ten companies control, almost exclusively, every large food and beverage brand in the world. These companies, including Nestlé, which procured 477,000 tonnes of soy in 2017 (almost 80% of which is used to feed livestock), hold the key to systemic change on supply chains and agriculture-induced carbon emissions. The corporate investment sector not only plays a huge role in driving climate change, but also has a role to play in reducing it. The shift between short-term profitability and the need to reduce emissions is presenting in a steady upward trend in the Sustainable and Responsible Impact (SRI) investment sector. The larger problem remains, however, that global agribusiness is defined in a world driven by unsustainable material growth and accumulation by dispossession.

To halt deforestation, water shortages and pollution from overuse of fertilizers, governments must be pressured to shift away from pro-agribusiness policy frameworks and move toward increasing environmental regulations. Though climate change litigation can be used as a corporate tool to quash environmental regulation, it is increasingly a method used to bring pressure to bear on a nation-case level, with agriculture-based emission cases just beginning to emerge, and pro-regulatory recommendations beginning to find their way into agriculture and energy policy recommendations and blueprints. These are all supply-side target strategies that can be employed at a policy level to mitigate climate change.

From a civic action perspective, there are several strategies which may also prove useful. Demand-side strategies include initiatives for reducing food waste and shifting dietary trends. Cross-cutting strategies include civic mobilizations that push for legislative changes to agricultural subsidies and trade agreements, or climate change legislature overhauls. Consumer awareness campaigns are leading to divestment and reinvestment in sustainable investment markets, environmental networks are working to create supply chain transparency, and remote-sensing studies are expanding carbon databases that act as watchdog devices. These are but a few of the areas that research initiatives can focus on when considering assembling frameworks for agricultural project or educational toolkit designs.

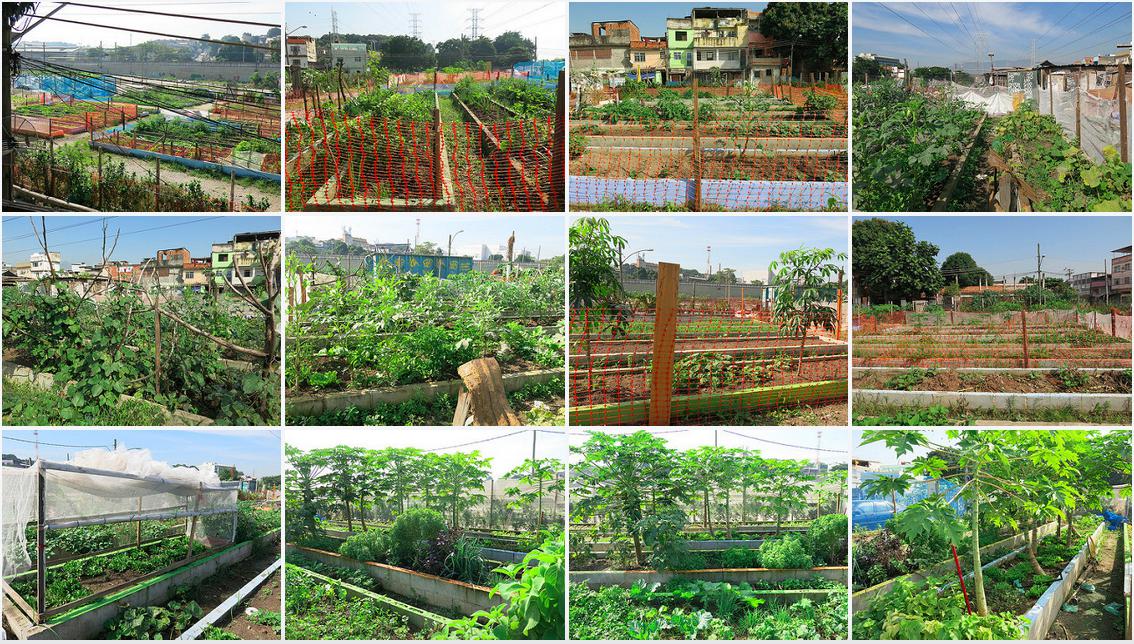

On a micro or municipal level, there are numerous actions, mobilizations, organizations and networks that are working to ensure the Right to Food using sustainable farming methods. The informal economy comprises more than half of the global labor force and more than 90% of micro and small business enterprises worldwide. Hundreds of millions of people pursue their livelihoods in conditions of informality, where food takes up the majority of either their time or their income. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization has long recognized the important contribution of small farmers who produce using agroecology methods, though the informal sector’s contribution and potential contribution in this area remains, for the most part, neglected.

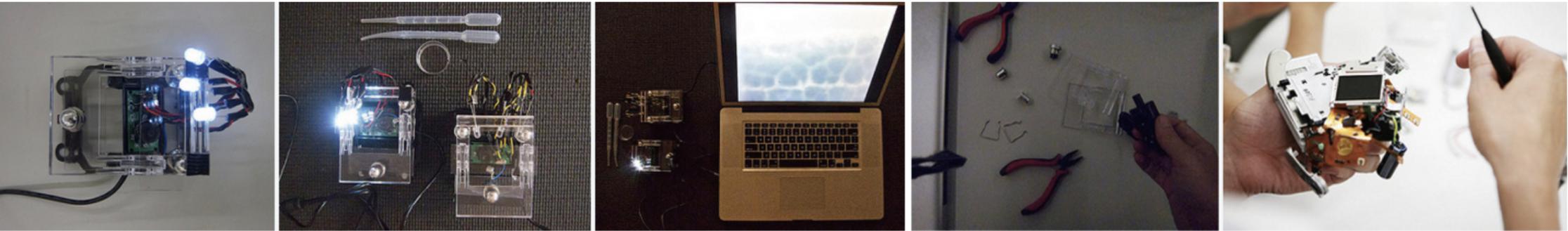

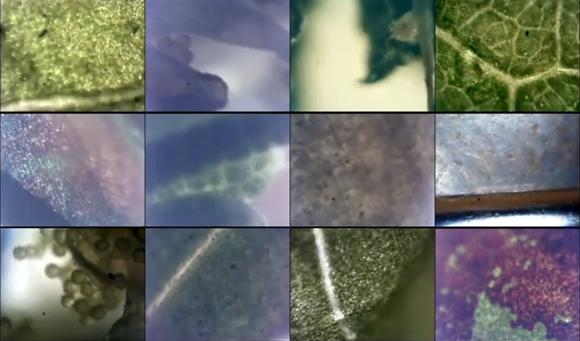

My own work has focused on co-producing organic urban gardens with the informal sector in Brazil. I’ve worked with DIY media kits to hack old webcams and produce microscopes to study plants with functionally literate children, conducted farm-to-table workshops, and created children’s gardens from sites that had to be remediated by clearing of tons of garbage before we begin. Not only is there a need to work from the bottom-up, or as a facilitator between formal and informal societal tiers, but also with youth at key vulnerable ages (before they become locked into a particular life track) to help instill knowledge, skills, and a sense of possibility for living healthier, more fulfilling lives. This provides increased opportunities for positive role models and community leaders to emerge to recraft environments that are historically marred by conflict, oppression, poverty and State abandonment into fields of care.

Indigenous communities have a lot to offer when rethinking our relationship to agriculture and the environment. They have a good understanding of how ecological destruction is entangled with land thefts and colonization and have pragmatic and compelling perspectives on how to integrate agriculture with sound environmental management. Across the globe, multitudes of small-scale agroecology investments in water and land sectors draw on indigenous social capital to actively protect water supplies and sustainably manage livestock and crops. My own experience led me to work with community and indigenous leaders to create biomedicinal teaching kits that were used as an interface and departure point for working with underserved youth in Rio de Janeiro and Bahia.

Medicinal Seed Bank is a databank project, lecture series and field teaching program used for studying medicinal seed samples. It was designed in conjunction with the Medicinal Teaching Kit.

The value and purpose of these scenarios is not only to examine, but to reconfigure the complex interrelationships among diet, food production, environment, human health, and to aid in promoting self-agency in the face of the aggression these populations face. In order to advance an ecological perspective that reduces threats to the health of the public and to the biophysical environment, we must engage on all levels.